Blog & News

Reporting Requirements Related to Unwinding Medicaid Continuous Coverage: Considerations for Medicaid and the Marketplace (State Health & Value Strategies Expert Perspective Cross-Post)

February 9. 2023:The following content is cross-posted from State Health & Value Strategies.

Original publication date: February 9, 2023.

Authors: Elizabeth Lukanen, Emily Zylla, SHADAC

The Families First Coronavirus Response Act implemented a Medicaid continuous enrollment requirement which was enacted to preserve coverage during the COVID-19 public health emergency and has resulted in a sharp increase in enrollment. Since February 2020, enrollment in Medicaid and the Children's Health Insurance Program (CHIP) has increased by 20.2 million enrollees. When the unwinding of the Medicaid continuous coverage requirement begins, it will represent the largest nationwide coverage transition since the Affordable Care Act. As states restart eligibility redeterminations, millions of Medicaid enrollees will transition to other coverage and some will become uninsured. Now that the details and timing associated with the unwinding of the Medicaid continuous enrollment requirement have been established by the Consolidated Appropriations Act, 2023 (CAA), states can start refining and implementing long laid plans to restart eligibility redeterminations and return to routine eligibility and enrollment operations.

As part of this process, states will be required to closely track and monitor the impacts of the resumption of eligibility redeterminations and disenrollments and to make that data public. The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services’ (CMS) commitment to transparency is mirrored by calls from advocates and researchers eager to see how progress is being made as people enrolled in Medicaid have their eligibility redetermined. This expert perspective outlines the relevant reporting requirements that were included in the CAA and the corresponding reporting guidance provided by CMS in its January 2023 State Health Official letter, and presents considerations for state officials as they fulfill their federal obligations and address calls from advocates and others for transparency.

Reporting Requirements During Unwinding

The Consolidated Appropriations Act, 2023 established a set of reporting requirements related to unwinding that will, for the first time, be made publicly available by CMS. Box 1 provides an overview of the CAA required reporting indicators. CMS believes that all of the measures overlap with indicators Medicaid/CHIP agencies and state-based marketplaces (SBMs) are currently required to report, including as part of: the monthly Unwinding Data Report (outlined in a March 2022 State Health Officer letter and detailed in subsequent Data Specifications; through existing Performance Indicators and T-MSIS submissions; or via existing SBM Priority Metrics.i Therefore, CMS does not anticipate that states or SBMs will need to submit a separate report (or additional reporting) to comply with the new CAA requirements. Additionally, CMS plans to report on behalf of states that use the federal eligibility and enrollment platform (FFM states) as well as SBMs on the federal platform (SBM-FP states).

Although there is no new data reporting being required, the indicators that states report will be made public for the first time; in addition, there are new enforcement provisions and penalties for noncompliance. Reporting and enforcement provisions released as part of the CAA start on page 3,859, and more detail is available in a CMCS Informational Bulletin from January 5, 2023 (“Key Dates Related to the Medicaid Continuous Enrollment Condition Provisions in the Consolidated Appropriations Act, 2023”) which also revises due dates for existing unwinding reports such as the Renewal Distribution Planii (due February 1, 2023 for states initiating renewals in February or February 15, 2023 for all other states ) and the Baseline Unwinding Report (due the eighth day of the month in the month that the state initiates renewals). Additional reporting requirement information is also available beginning on page 17 of the January 2023 SHO letter.

| Box 1. CAA Required Monthly Indicators and Data Sources | |

|---|---|

| Reporting Element | Mode of Submission |

| Medicaid/CHIP Indicators | |

| Applies to all states | |

| · Total number of renewals initiated | Monthly Unwinding Report, Metric 4 |

| · Total number of successful renewals | Monthly Unwinding Report, Metric 5a |

| - Number of ex-parte renewals | Monthly Unwinding Report, Metric 5a(1) |

| · Total number of coverage terminations | Monthly Unwinding Report, Metric 5b & 5c |

| - Number of procedural terminations | Monthly Unwinding Report, Metric 5c |

| · Total number enrolled in a separate CHIP | T-MSIS, CHIP-CODE |

| · Total call center volume | Medicaid/CHIP Performance Indicator 1 |

| · Average wait times | Medicaid/CHIP Performance Indicator 2 |

| · Average abandonment rate | Medicaid/CHIP Performance Indicator 3 |

| Marketplace Indicators | |

| Applies to states that use the federal eligibility and enrollment platform | |

| · Total number of individual accounts received at the marketplace from Medicaid/CHIP due to a redetermination | N/A—CMS plans to report on behalf of states with FFMs and SBMs on the federal platform (SBM-FPs). |

| - Number determined eligible for a qualified health plan (QHP) | |

| - Of those determined eligible, number who selected a QHP | |

| Applies to states that use an SBM without an integrated eligibility system | |

| · Number of individuals whose accounts are received by the SBM or basic health program (BHP) | Monthly SBM Priority Metrics, 7a & 7b |

| - Number determined eligible for a QHP or BHP | Monthly SBM Priority Metrics, 9a & 172a |

| - Of those determined eligible, number who selected a QHP or enrolled in a BHP | Monthly SBM Priority Metrics, 1a & 169a |

| Applies to states that use an SBM with an integrated eligibility system | |

| · Number determined eligible for a QHP or a BHP | Monthly SBM Priority Metrics, 9a & 172a |

| - Of those determined eligible, number who selected a QHP or enrolled in a BHP | Monthly SBM Priority Metrics, 1a & 169a |

| Important Notes: · CMS also reserves the right to add reporting metrics, if needed, in the future. · The CAA specifically indicates that these data should be reported monthly from April 1, 2023 through June 30, 2024 and that they will be made publicly available. · Failure to comply with the reporting requirements is associated with penalties, which include regular FMAP reductions and the necessity of a corrective action plan (See Enforcement and Penalty section below). · States should also continue to report other related Medicaid data; this was highlighted in recent CMS guidance. This includes Medicaid and CHIP eligibility and enrollment Performance Indicators as well as the submission of state files to the Transformed Medicaid Statistical Information System (T-MSIS). · Currently, the standards to qualify as an integrated eligibility determination system are undefined. · The CAA also requires a one-time submission of systems readiness artifacts that include configuration plans (e.g., Implementation Plan), testing plans, and test results. System readiness artifact documents should be based on state or vendor developed formats. CMS templates will not be provided. Details on what should be included in the readiness documents and how these documents should be submitted are outlined in a refresher document released by CMS in January 2023. |

|

Reporting Timeline

Although CMS expects states will be able to meet the reporting requirements outlined above through existing reports and tools, the timing of certain state reporting may need to change in order to meet the requirements of the CAA. See Box 2 for an overall reporting timeline. All states will now have to submit monthly unwinding data reports from April 1, 2023 through June 30, 2024. This means that states who initiate their first batch of renewals in February 2022 will now have to submit monthly unwinding data for a period that exceeds 14 months.

| Box 2. Reporting Timeline | ||

|---|---|---|

| Requirement | Due Date | |

| States Initiating Renewals in February | States Initiating Renewals After February | |

| Renewal Distribution Plan | 1-Feb-23 | 15-Feb-23 |

| Systems Readiness Artifacts | 1-Feb-23 | 15-Feb-23 |

| Baseline Unwinding Data Report | 8-Feb-23 | Eighth day of the month in which renewals begin |

| Monthly Unwinding Data* Reports | Eighth day of the month during unwinding through June 30, 2024 | |

| Monthly Performance Indicators* | Eighth day of the calendar month | |

| SBM Priority Monthly Metrics* | TBD | |

*Reporting overlaps with requirements in the CAA.

Note: Should the eighth calendar day fall on a weekend or holiday, states may submit by the next business day.

Enforcement and Penalty

To assure transparency and timely reporting, the CAA includes penalties for states that do not meet the reporting requirements (Box 3). Most notably, if a state does not report the required data starting in July 2023, it will face a reduction in the state’s Federal Medical Assistance Percentage (FMAP) by .25 percentage points for each quarter in which the state fails to satisfy the reporting requirements (up to a maximum of one percentage point). The full set of penalties associated with non-compliance are summarized below and were presented in a State Health and Value Strategies webinar, “Omnibus Unwinding Provisions and Implications for States.”

| BOX 3. | ||

|---|---|---|

| The CAA vests CMS with targeted oversight and enforcement powers related to unwinding. These enforcement mechanisms extend beyond the ability for CMS to eliminate the enhanced FMAP for states that do not meet required conditions. | ||

| Penalty | Trigger | Notes |

| 1) Regular FMAP reduction for failure to report required information | CMS determines that for the period from July 1, 2023 through June 30, 2024, a state fails to comply with the CAA reporting requirements. | A state’s FMAP for the quarter will be reduced by 0.25 percentage points, plus an additional 0.25 points for each prior quarter of noncompliance (not to exceed 1 percentage point). |

| 2) Corrective Action Plan | CMS determines that for the period from April 1, 2023, through June 30, 2024, a state has failed to comply with: - The CAA reporting requirements; or - Any “federal requirements applicable to eligibility redeterminations.” |

The legislation establishes timelines for timely submission, CMS approval, and implementation of the CAP. |

| 3) Suspension of procedural terminations* and/or civil monetary penalties of up to $100,000 a day | CMS determines that a state has failed to submit or implement its corrective action plan. | It remains to be seen how and the degree to which CMS will exercise these enforcement actions and how states will respond. |

*Procedural terminations occur when potentially eligible individuals fail to respond to a state Medicaid/CHIP agency’s request for additional information as part of the redetermination process.

Consideration for Unwinding Reporting Requirements for States

As states prepare for the unwinding of the continuous coverage requirement and the implementation of new required reporting activities, they should consider ways to demonstrate and communicate progress with key partners. The following strategies will ensure transparency to stakeholders, who will be critical in supporting coverage retention for eligible enrollees, while also keeping policymakers informed about the success of this transition.

| Seek technical assistance from CMS or SHVS to improve reporting. States that are unable to submit data as defined are directed to check a box labeled “Unable to Report” and include an explanation of why the state cannot report the metric. Guidance goes on to say that CMS may follow up to discuss further. States that cannot report these baseline metrics can take advantage of any technical assistance that CMS offers in order to improve the reporting of this data. Without this minimum, up-to-date data, states, policymakers, advocates, and other key stakeholders lose the opportunity to identify barriers that populations may be facing to enroll or renew their Medicaid coverage, as well as opportunities to identify effective solutions. SHVS is also available to support states through technical assistance. Please contact Heather Howard at heatherh@princeton.edu. |

Coordination Between Medicaid and Marketplaces. The reporting requirements in the CAA include measures from both Medicaid and the marketplace. At a minimum, state Medicaid agencies will want to coordinate with their state-based marketplace (SBM) or the federally facilitated marketplace (FFM) on metrics that affect both groups, such as call center data or information on the number and outcomes of electronic transfers. For states in which the same agency operates its Medicaid program and the SBM, there may be fewer barriers to coordinating the data, but all states should align to operationalize how and when the data are shared with the public. Pre-planning and coordination in advance of the first report can help streamline staff effort and reduce confusion.

Sharing Relevant Information Publicly. The CAA clearly states that metrics submitted to monitor eligibility redeterminations will be made publicly available. Details on how and when these data will be shared with the public are forthcoming, but states should expect this and consider releasing their own communications to ensure accurate interpretation of their data and to provide context about their successes and challenges. This could include measures required for the unwinding as well as Performance Indicator data that could help serve as an early warning sign as to how applicants and enrollees are faring on renewals and redeterminations. States will likely face requests for information from advocates and researchers who have already called for increased transparency. By publishing information on retention and disenrollment, successful transitions to new coverage, and changes to the numbers and rates of uninsured, states can meet these information needs in an organized and timely way while also controlling their data and message. Some states, such as Utah, are considering publishing new Medicaid enrollment and retention dashboards that would track this type of data in more easily digestible, visually appealing ways, and we encourage states to explore that possibility. SHVS will continue to monitor state activities in this area and will plan additional programming or publications as public dashboards become available.

Consider Reporting Data That Is Disaggregated Beyond What CMS Requires. The CMS guidance does not require states to report data disaggregated any further than by modified adjusted gross income and non-disability applications versus disability applications. Data broken down by various population characteristics (e.g., age, race/ethnicity, income, gender, language, or program type) or geographic areas make it easier to understand the disproportionate impact enrollment and renewal policies have on groups that have been economically and socially marginalized. States can prioritize the monitoring and reporting of disaggregated data even though CMS has not required it. At a minimum, we recommend displaying data breakdowns by program type, age, race, ethnicity, and geography (ZIP code is best, but county or region is also helpful). States should also consider additional breakdowns as the data is available, such as by language, income, and disability status. Data reported in this way would help improve the transparency, accountability, and equity of the Medicaid program.

Consider the Guidelines a “Floor” and Expand Monitoring Measures to Get Better Insights Into Unwinding. The reporting requirements and resources from CMS set the minimum amount of reporting that all 50 states should produce. For states with the bandwidth and resources, additional analysis could include an in-depth study of churn during this period or for specific groups, or an evaluation of outreach and enrollment strategies designed to identify what worked to keep people enrolled (e.g., color letter campaigns, assister training, ad campaigns, etc.). States could also assess coverage transitions and reasons for and consequences of disenrollment by fielding a disenrollment survey. This could provide quantitative and qualitative data that could be used to understand both enrollees’ experiences navigating Medicaid processes as well as the consequences of disenrollment.

Blog & News

Issue Brief: Unwinding the Medicaid Continuous Coverage Requirement - Transitioning to Employer-Sponsored Coverage (State Health & Value Strategies Cross-Post)

January 2023:The following content is cross-posted from State Health and Value Strategies, published on January 19, 2023.

Authors: Elizabeth Lukanen and Robert Hest, SHADAC

Medicaid and the Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP) have played a key role in the response to the COVID-19 pandemic, providing a vital source of health coverage for millions of people. The Families First Coronavirus Response Act (FFCRA) implemented a continuous coverage requirement in Medicaid, coupled with an increase in federal payments to states. The requirement has prevented states from disenrolling Medicaid enrollees, except in limited circumstances, allowing millions of Americans continued access to healthcare services during the pandemic.

Enrollment in Medicaid and CHIP has grown sharply since February 2020, with more than 20 million enrollees added to state rosters as of September 2022. Continuous coverage can also likely be credited for the decrease in the number of people who were uninsured in 2021, down to 8.6% from a pre-pandemic level of 9.2% in 2019. This was driven by a 1.4 percentage point increase in public coverage in 2021, to 36.8% from 35.4% in 2019. These trends were mirrored across states, with 28 states experiencing significant decreases in their rates of uninsurance. Meanwhile, 36 states saw rising rates of public coverage with none seeing a decline in public coverage.

When the unwinding of the Medicaid continuous coverage requirement begins, states will restart eligibility redeterminations, and millions of Medicaid enrollees will be at risk of losing their coverage. Estimates vary, but most approximate that in the range of 15 million to 18 million people will lose Medicaid coverage, with some portion exiting because they are no longer eligible, some losing coverage due to administrative challenges despite continued eligibility, and some transitioning to another source of coverage. While much attention has been paid to how states can approach the unwinding of the continuous coverage requirement to prioritize the retention of Medicaid coverage and transitions to marketplace coverage, less attention has been paid to the role of employer-sponsored insurance.

To get a sense for the size of the group that might have employer-sponsored coverage as an option, this issue brief discusses the proportion of individuals with an offer of employer-sponsored coverage by income and state, and the proportion of those offers that are considered affordable based on premium cost. The issue brief also discusses the importance of a Medicaid disenrollment survey to monitor the coverage transitions associated with the unwinding.

A companion issue brief, Helping Consumers Navigate Medicaid, the Marketplace, and Employer Coverage, discusses how state Medicaid agencies, state-based marketplaces, labor departments, and employers can play critical roles in helping people understand and navigate their employer coverage options.

To support communications efforts during the unwinding, SHVS has also produced sample messaging for state departments of labor to share with the employer community which explains the unwinding and coverage options for employees.

Blog & News

Expert Perspective and Issue Brief: Tracking the Data on Medicaid’s Continuous Coverage Unwinding (State Health & Value Strategies Cross-Post)

January 21, 2022:The following content is cross-posted from State Health and Value Strategies published on January 21, 2022.

Authors: Emily Zylla, Elizabeth Lukanen, and Lindsey Theis, SHADAC

Medicaid and Children’s Health Insurance Plan (CHIP) programs have played a key role in the response to the COVID-19 pandemic, providing a vital source of health coverage for millions of people. However, when the Families First Coronavirus Response Act (FFCRA) Medicaid “continuous coverage” requirement is discontinued states will restart eligibility redeterminations, and millions of Medicaid enrollees will be at risk of losing their coveragei.

A lack of publicly available data on Medicaid enrollment, renewal, and disenrollment makes it difficult to understand exactly who is losing Medicaid coverage and for what reasons. Publishing timely data in an easy-to-digest, visually appealing way would help improve the transparency, accountability, and equity of the Medicaid program. It would inform key stakeholders, including state staff, policymakers, and advocates, allowing them to more fully understand the impacts of Medicaid policy changes on enrollees’ access, and give them an opportunity to modify or implement intervention strategies as needed. States already collect a significant amount of data that could inform their success in enrolling and retaining eligible individuals in Medicaid. Many advocates and researchers have been calling for increased transparency around this data in order to better understand the barriers and challenges individuals face when trying to enroll in or maintain coverage.

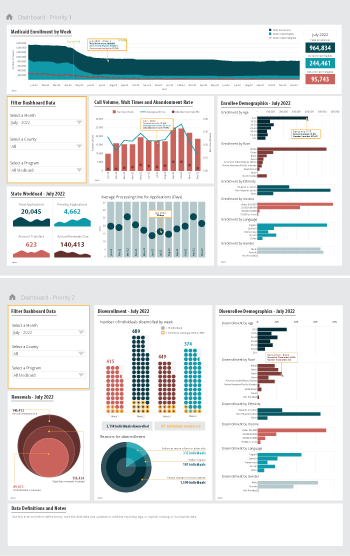

One effective way to monitor this dynamic issue is by creating and publishing a Medicaid enrollment and retention dashboard. A typical data dashboard is designed to organize complex data in an easy-to-digest visual format, thus allowing the audience to easily interpret key trends and patterns at a glance. A new issue brief examines the current status of Medicaid enrollment and retention data collection, summarizes potential forthcoming reporting requirements, and describes some of the best practices when developing a data dashboard to display this type of information.

The issue brief lays out a phased set of priority measures and provides a model enrollment and retention dashboard template that states can use to monitor both the short-term impacts of phasing out public health emergency (PHE) protections and continuous coverage requirements, as well as longer-term enrollment and retention trends.

State Medicaid Enrollment and Retention Dashboard – Measurement Priorities

Priority 1 – Use currently reported data: Start with the data that are already collected and submitted to the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) under the 11 Medicaid performance topics.

Priority 1 – Use currently reported data: Start with the data that are already collected and submitted to the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) under the 11 Medicaid performance topics.

Priority 2 – Track reasons for disenrollment: Include measures in the proposed Build Back Better Act (BBB) legislative language that address the reasons why people are being disenrolled.

Priority 3 – Monitor coverage transitions: Add measures to address issues of transitions between programs and churn—the moving in and out of coverage—that frequently occurs in Medicaid and CHIP.

Priority 4 – Explore reasons for and consequences of disenrollment: Field disenrollment surveys that could provide quantitative and qualitative data that could be used to understand both the enrollee’s experience navigating Medicaid processes as well as the consequences of disenrollment.

Regardless of the measures highlighted, an overarching goal of any Medicaid enrollment and retention dashboard should be a focus on displaying disaggregated data. Providing data broken down by various population characteristics (e.g., age, race/ethnicity, income, gender, language, or program type) or geographic areas (urban, rural) will make it easier to understand the potentially disproportionate impact of administrative enrollment and renewal policies on communities of color, persons with lower incomes, and other populations that face disparities. Access to this type of granular data provides stakeholders an opportunity to take action in order to minimize needless loss of coverage.

Designing an easy-to-understand dashboard that is accessible to all interested stakeholders—state or county program staff, navigators or enrollment assisters, and advocates—will highlight the early warning signs of large numbers of people losing Medicaid coverage. States should start small, using data dashboard best practices and as they gain experience publicly reporting this data, consider adding additional measures over time.

i Buettgens, M. & Green, A. (September 2021). What Will Happen to Unprecedented High Medicaid Enrollment after the Public Health Emergency? [Research report]. Urban Institute. https://www.urban.org/sites/default/files/publication/104785/what-will-happen-to-unprecedented-high-medicaid-enrollment-after-the-public-health-emergency_0.pd

Pages

- « first

- ‹ previous

- 1

- 2

- 3